Sometimes, hardware projects get cancelled before they have a chance to make an impact, often due to politics or poor economic judgment. The Tsushin Booster for the PC Engine is one such project, possibly the victim of vicious commercial games between the leading Japanese console manufacturers at the tail end of the 1980s. It seems like a rather unlikely product: a modem attachment for a games console with an added 32 KB of battery-backed SRAM. In addition to the bolt-on unit, a dedicated software suite was provided on an EPROM-based removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

Internally, the Tsushin booster holds no surprises, with the expected POTS interfacing components tied to an OKI M6826L modem chip, the SRAM device, and what looks like a custom ASIC for the bus interfacing.

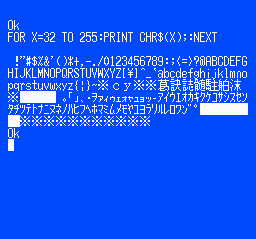

It was, however, very slow, topping out at only 1200 Baud, which, even for the period, coupled with pay-by-minute telephone charges, would be a hard sell. The provided software was clearly intended to inspire would-be games programmers, with a complete-looking BASIC dialect, a comms program, a basic sprite editor with support for animation and  even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

PC Engine hacks are thin pickings around these parts, but to understand a little more about the ‘console wars’ of the early 1990s, look no further than this in-depth architectural study. If you’d like to get into the modem scene but lack original hardware, your needs could be satisfied with openmodem. Of course, once you’ve got the hardware sorted, you need some to connect to. How about creating your very own dial-up ISP?